Game Dev Noob: Playtesting, Prototyping, and the Art of the Playspace

Even the most basic decisions can shape how we design a game... as long as we remember to playtest.

Most people begin thinking about a game’s design in terms of its themes or mechanics. Me, Nicholas? I wanted to think of UrbanPlan as manipulating objects with your hands.

Now in all honesty, you could argue that this too is a mechanic. Maybe it’s because I’ve been on the floor cutting out index cards with my daughter that I only “began” thinking about my process in this way. And like many developers, I’m realizing that I began my process almost—by accident.

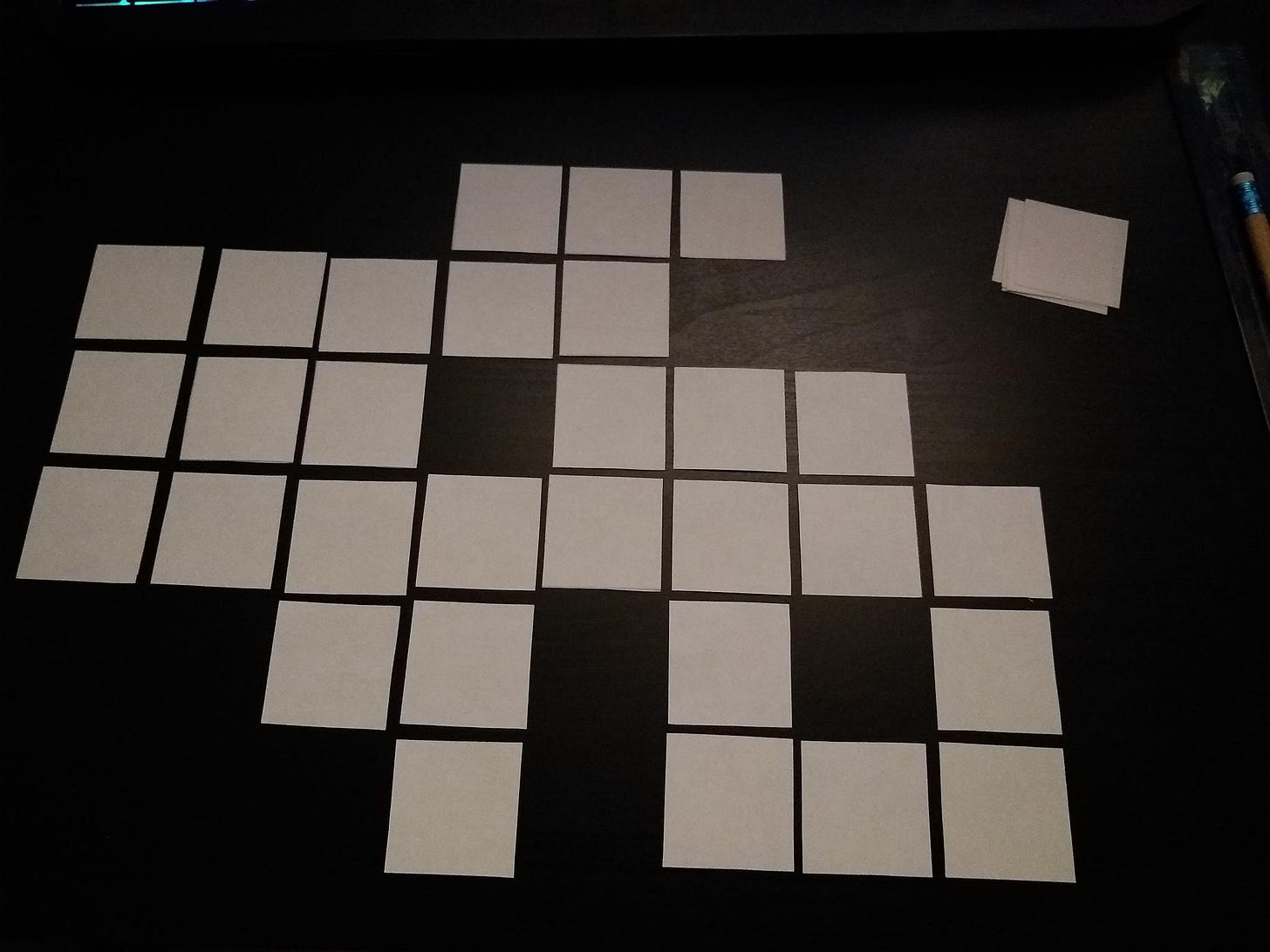

When I started, I already had the basic shape of an idea and theme formed in my head. So it’s hard for me to think of that as the beginning, because it wasn’t until I actually started cutting out pieces of paper for the prototype below that I encountered my first major game design decision.

Emergent design: why they keep saying “playtest”

In our previous post, my notes showed an image of the playspace as a fixed grid. Players would fill that grid out with tiles and form their own urban plans that would directly coincide with other players in that space. While not intrinsically a PVP or a PVE experience, it would support both modes.

I did this not just to make players submit to some rigid order of play, but also because my house doesn’t have a table big enough for a massive board and all its bits and bobs. No matter how much I love the game Scythe, my biggest pet peeve with it is how in my house we have to play it on the floor. So yes, there I was, treating a table like a hardware constraint. I was afraid that if I let my game be more freeform and allow players to put tiles wherever, that it could easily sprawl out into a state where the playspace might not even fit on a huge banquet table. But that word—sprawl—it finally clicked in my head!

“City sprawl” is a feature of city planning, even if it is (in the real world) an unintended one.

Sprawl is generally regarded as a negative feature of cities. Cities sprawl to accommodate an influx of new residents, or so people can achieve that dream of a single family home—it’s a whole debate, but it is something they do. As a grid, my “cities” couldn’t sprawl, and if my players wanted them to—if I was truly going to create communicative mechanics—mechanics that convey meaning inherently by using them—then isn’t the sprawliness of gameplay something I needed to at least consider as a designer?

So, I cut out a bunch of 1”x1” squares of paper and started playing them on my desktop according to a basic set of rules I made up on the fly. This was the game’s first prototype and my absentminded arrangement of tiles the very first playtest. How would I structure them? How would other players? This radically changed how I wanted the playspace to look and feel. I still wanted to avoid the Scythe problem, because I hate it, but this first playtest reminded me that my game was different in a key way.

Scythe’s board is massive, but it’s also fixed. Which makes the board irrelevant. UrbanPlan is not fixed, and it is about the board you’re creating.

The game begins as a single tile, and the size and shape of the playspace are an emergent property of gameplay. It means that the constraints of where you play in the world have some influence on how things play out. In my first playtest, I found myself not wanting to place tiles too far down, because they were coming closer and closer to the edge of my desk.

What I saw emerging before me, through both my conscious and unconscious actions—only in retrospect did I acknowledge I was avoiding the edge—was something like the plan of a city. Where in real life, it can sprawl out in odd ways and have arbitrary constraints placed on its boundaries (e.g. mountains and ravines), I had table corners and couch cushions.

At this point in UrbanPlan’s design, there’s no art, no numbers, barely any rules, and yet I can see something, something, emerging in the design that I wouldn’t have, if I hadn’t started to play it.

Tangrams and Puzzle Design

On a recent episode of the Furidashi Podcast,1 we talked about the importance of thinking about tabletop games as the manipulation of a shared playspace. Many TT games have a puzzle feel or puzzle-like qualities to them: even as a group, you’re trying to make everything fit together in a particular way.

UrbanPlan’s design has these qualities as well. There are incentives for players to want to place tiles in a relatively tight manner (maybe adjacency bonuses?), and there are reasons not to (negative adjacency bonuses!). This is my model for player choice in-game. Something that takes place within meaningful constraints, whether it’s the tabletop or your opponent. You shouldn’t want to place a tile wherever you feel like it.

Placing the tile is a puzzle you want to solve on every single turn.

Trying to dissect that, my mind immediately wandered to the tangram,2 a so-called dissection puzzle that I remember playing very early in life. This is common at young ages: putting squares into square shaped holes and triangles into triangle shaped holes. “Shape play” is the way we learn how things go together and not merely independent of one another.

Tangram is interesting, precisely because, much like words and language, you can treat it like a puzzle, where you try to make the pieces fit into a predetermined outline, but you can also use those same pieces to create novel designs of your own making. It’s like Lego: you can follow the instructions to build the set you bought or throw the instructions away and do whatever.

Urban planning is itself much like a tangram problem. There may be some grand design at work, in the form of comprehensive plans, district plans, and zoning codes, but because a city is something that unfolds over time, city planners have to make incidental design pieces work within that larger frame. One developer comes along and wants to build a shampoo factory with good access to the highway, but there’s a school where they want to site the property, so a planning and zoning commissioner have to think about whether to reject the plan outright or work with the developer to put it on the other side of town.3

Maybe you, as an apartment dweller in an expensive part of town, would have preferred to be building housing in a part of the city with old, abandoned industrial sites. But no developer has stepped up to do so. As part of the planning process, you have to work with what you have. A hexagon might be ideal for the tangram design you have in your mind—but there simply is no hexagon in the set.

Which is to say, no, I’m not using hexes. I like squares!

So, week 2: what Have We Learned So Far?

I’m making a tabletop game, so it makes sense that “paper prototyping” would be valuable. But Lauryn constantly encourages paper design before even getting into a game engine, and now I can see why:

There is meaning in gameplay, even before you have the language to describe it.

Simply by doing things with your hands and placing objects in particular ways can communicate something to you, as the designer, that you hadn’t considered before. Maybe it was a “given” of the game, or maybe it was an “assumed” decision that isn’t safe to assume at all. As game designers, we can’t just let this flow over us. We have to be able to recognize the decisions we’re making as we make them, or we—as designers—aren’t making meaningful choices. So how can we expect our players to make them meaningful?

You have to be able to recognize it, as it happens, and make sense of it so as to be able to reproduce it.

Next time, we’ll examine this communicative aspect of gameplay from the perspective of the particular roles the players of UrbanPlan will be asked to inhabit.

Until then, we’ll see you on the podcast!

A puzzle/game of Chinese origin made up of seven pieces: five triangles of varying sizes, a square, and a parallelogram. Typically, you learn how to arrange these pieces to form a square, but more elaborate tangram problems often have you make rudimentary images like a fox or a monk.

Important, because Urban Plan is also a role-playing game. My goal is to make players take on those roles that help (or hinder) their decisions during the game. So this is a very illustrative example, as it is literally what you’ll be expected to do in game.