Establish - Level Design and Narrative Mapping

How to establish Character, Dramatic Situation, and Articulations at the onset of a level or game as a whole

So, in our previous post, we noted at the end how this time around we would be diving into the vast complicated middle of our Establish - Complicate - Resolve paradigm for narrative mapping and level design. In retrospect, it seems, instead of starting in the middle, we should begin at the beginning. With that in mind, we want to look at three broad categories with regard to the kinds of things you want to clearly establish for the player in order to avoid confusion in gameplay:

Character - who you are in a given gameplay moment and what the relationship between this who and other characters is in the game or level

Dramatic Situation - broadly speaking, what the player is meant to know and what they are meant not to know; also, signaling the player’s situation with regard to micro and macro conditions in game

Articulations - establishing what can be interfaced with in game, as well as how objects and systems interact or articulate with one another

Before we deal with each of these in turn, though, we want to suggest that, when establishing the general contours of an encounter, level, or even an entire game, you shouldn’t shy away from revealing things to your player. It might seem tempting to hold back for an inevitable big reveal, but this is, in fact, a risky gimmick that can distract from core gameplay and leave the player feeling untethered from their experience. We’re not saying you should never do it, but consider the possibility that how something is revealed is just as, if not more important than what is revealed.

Take Romeo and Juliet, for instance, a play that is somewhat known for its shocking double suicide, yet, at the very beginning, a guy (or chorus) comes out on stage and, in the prologue, spoils the whole thing. This doesn’t ruin the experience of watching what unfolds, because, in theater as with games, the play’s the thing. In fact, knowing what will happen has important, empathetic effects. As we observe our star-crossed lovers fall in love, their romance is tinged with a melancholy that wouldn’t be there, if we didn’t know what was about to befall them.

At its core, the establishment phase should be about creating the parameters in which the player is meant to understand what follows. That state doesn’t have to be one of pure ignorance.

So, with that in mind, let’s dive in!

Character and Relationships

At the beginning of a game, there are a number of who questions that need to be resolved: who am I? Who are all these people telling me what to do? Who am I meant to become? etc.

What’s peculiar about games is how, because you rarely get to speak for yourself outside of predetermined dialogue trees, who you are is largely communicated to you through interactions with other characters and with environments. There is a broad tendency within video games to present the player character as something of a conceptual blank or, at best, a rough sketch of a person with a name attached to them (*cough*Link*cough*).

The reason for this is devs often want the player to have a greater say in who this character becomes through their in game decisions. Thus, in RPGs in particular, the player character is more a framework that the player fills out through their own choices regarding abilities, spells, attributes, and so forth, much like a character sheet. A great deal can be said about what goes into character design, and if that’s something you’re interested in, our current Furidashi Classroom course deals with it in greater detail. However, for the time being, we want to think about characters’ narrative function, particularly at the onset of gameplay.

At the very beginning of Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare, we’re introduced to Gaz and Captain Price, iconic characters who serve a common, recognizable function in action games: to provide the player with objectives and generally guide the narrative flow of being a murder hobo. At this initial stage, however, they serve primarily to establish who you are both in terms of the game’s story elements but also with regard to various fundamental systems.

The Newbie

As you enter the hangar where the game’s first challenge, a training course, has been set up, Price and Gaz engage in some gentle ribbing of their new recruit, namely you. Though the game is, in many respects, a very serious primer on how to do war crimes, this friendly banter establishes how not everything that is to follow is going to be grim and dark. In fact, this lighthearted moment shows how there will be a clear contrast within and between story beats, as the very first thing you are tasked with after this moment, is to go through the training course, which simulates various engagement scenarios like shooting enemies behind cover, navigating tight corridors, and clearing rooms with flashbangs before moving in.

Though you do the course solo, the whole encounter is clearly contextualized within your place in the squad. As you enter the course, there is a board containing other squaddies’ times, and as you move into position, Price prompts you with a secondary objective of beating the fastest time. This isn’t just a list of to-do items, though. Each of these tasks is given meaning within the narrative framework of being characterized as a newbie. It spurs the player to maybe want to make Price and Gaz eat their words, beating the best time, and establishing the player as something more than just a fresh recruit. This motivation to excel exists, precisely because the framing for what is otherwise just a tutorial encounter imbues it not only with a sense of purpose but the initial inklings of a sense of camaraderie that will carry the player throughout the game.

This Is My Rifle, This Is My Gun

Gaz in particular serves another important establishing function, as the first guide to the relationship between character and weapon, or between player and core mechanics. Gaz introduces the player character, if they’re not already familiar, to the basic ranged and melee weapons, the rifle and knife, as well as to the unique mechanics of each, such as aiming down sights vs. shooting from the hip. Moreover, he introduces you to certain key environmental interactions, such as being able to shoot through some materials (e.g. wood) but not others (e.g. steel).

Gaz quickly runs the player through what could be characterized as a narrative sequence: a series of evolving tasks while firing down range. This sequence is a mainstay of most shooters, but there is a general principle at work that can be applied to a wide variety of games. Within the context of establishing the relationship between player and nonplayer characters, there is also the establishment of a relationship between character and game systems. As a result, what is basically a tutorial is stripped of some of the tedium that attends to such in game moments, and gives even skilled COD players a chance to shine rather than simply go through the motions.

For instance, the training course that serves as a tutorial for various siege mechanics also serves as a difficulty gauge. Rather than just have a menu item to choose a difficulty setting, the game allows the player to demonstrate their COD expertise through gameplay, and make a difficulty recommendation based upon it. Of course, you can always go into the settings and change things as desired, but this level of integration between systems provides value in the tutorial experience for a wide range of players. Moreover, it establishes a number of key settings and frames of reference that will persist throughout the game by means of gameplay rather than toggles buried in some arbitrary menu.

Dramatic Situation

As we can see, Modern Warfare is very upfront about what it is. Individual missions might contain some surprising moments, but within minutes, the game has stated pretty clearly what kind of game experience it’s going to be and how all those elements that make up the game center on the player character. However, it’s not all about you, and there’s a great deal within a game that goes on beyond the player that helps to establish who they are within certain micro and macrocosmic circumstances, as well as what is known and what is unknown to the player.

With this in mind, because we are academics at heart, we’d like to coin a phrase: ludonarrative irony. One of the major problems with Hocking’s concept of ludonarrative dissonance is the failure to recognize how the disjuncture between narrative and gameplay elements isn’t always a problem to be solved. If you recall our Romeo and Juliet example, the irony inherent in knowing the tragedy to befall the titular characters makes possible an emotional response that otherwise wouldn’t be all that salient. Far from a problem, then, irony is something that can enrich gameplay.

Irony is, at its most basic, a mismatch between something, like a statement or an event, and the broader circumstances surrounding it. A prince loudly proclaims his love for his brother, all the while the audience know that same brother is plotting his demise. With ludonarrative irony, we can think a bit more broadly, in gameplay terms, about what is revealed to the player, what is only partially revealed, and what is kept hidden. The interplay of these three creates a number of little ironies that the player will feel, almost viscerally.

Knowns and Unknowns

Because I am an old, I’m going to resist the temptation to make a Donald Rumsfeld joke, yet his bizarre schema of known unknowns and unknown unknowns is not entirely inept. The fog of war is a concept that is well understood in game design as a domain where the broad contours of a playscape are revealed to the player, while the details of what’s going on there in any given moment are kept hidden. The turn-based strategy series XCOM has always made excellent use of the fog of war, but there’s more to it than just concealing things from the player, because, when done well, the great unknown functions as a primary motivation, not just a vast veil.

When you load into a given XCOM mission, the interface reveals a great deal to the player, such as the position of your squaddies, their abilities, their ammo, their stealth condition, the rough location of objectives like a base or downed alien craft, among other things. You might spot an enemy grouping, known as “pods,” up ahead, and think it best to advance on them as quickly as possible. This is where the fog of war as motivation comes in. Our sniper Lauryn might want to advance on the pod via a northerly route, where she can take up a position on the high ground, but this brings her dangerously close to unknown parts of the map. Veteran XCOM players will know going that route runs the risk of activating additional pods, bringing them into the fight and quickly overwhelming your small squad.

Instead of a “known unknown,” it might be better to think of unknowns like the fog of war as visible or even legible. It doesn’t stop the player from engaging in certain forms of gameplay, but it does establish for the player something they might interpret and thereby influence their gameplay. In XCOM 2, there are “dark events,” where, you might not know exactly what is going on, but it certainly sounds bad, and you should probably do something to halt the progress of the avatar project. At the same time, you don’t have to intervene, or intervene just yet, and the game is revealing something to you in an only partialized form to influence your in game decisions without trying to overtly determine them.

Micro and Macro Conditions

Let’s say Lauryn, in her infinite wisdom, decided to take that northerly route, activated a pod of sectoids, who proceed to mind control her, and she takes out most of her squad from her new vantage point. You decide to evac the survivors, and head back to the Avenger, your mobile HQ, to figure out how you’re going to recover from this horrible setback. The irony of the player’s choice to risk it elicits a clear emotional reaction—you feel like crap—but it also has ramifications for larger conditions within the game. In this way, we can see how the interplay between microcosmic and macrocosmic situations create a peculiar feedback loop in which each keep re-establishing baseline conditions for the other.

Prior to the disaster mission, you might have thought you’d be moving on to the next major story mission, but having lost some of your best troops, you now need to take a step back and try to rebuild. Here we see an example of how the micro situation of a given mission has established entirely new parameters for how the more macro, management side of XCOM needs to be approached. Likewise, this new normal for the macro side means, on the micro level, you’ll need to be going on some easier side missions, so that you can level up a new squad to the point where you’ll be able to get back on track.

Here we can see how the disjuncture between a player’s expectations for progress and the reality of how things played out is not some fault in the game but rather the source of more interesting, emotionally engaging gameplay. There is, of course, a risk in building in too many setbacks for the player. They might get frustrated and simply stop playing. The key, then, is to think about the interplay of systems, narrative, mechanics, etc., for even though setbacks in XCOM can be quite extreme, the game always provides the player the means to recover.

Articulations

This interplay of game elements can be thought of as a system of systems or a system of articulations: the precise ways various elements work with and play off one another to create a variety of ways to play. When thinking about the establishment phase in a given level, we return to the concept of legibility. The interplay of elements needs, at minimum, to be visible to the player in such a way that they can interpret what it is they should or can do. A common player complaint in situations where the design could have used refining is that they “don’t know what to do.” It’s always possible that the player is just incredibly dense, but nine times out of ten, the game hasn’t perfectly established what actions it wants the player to take.

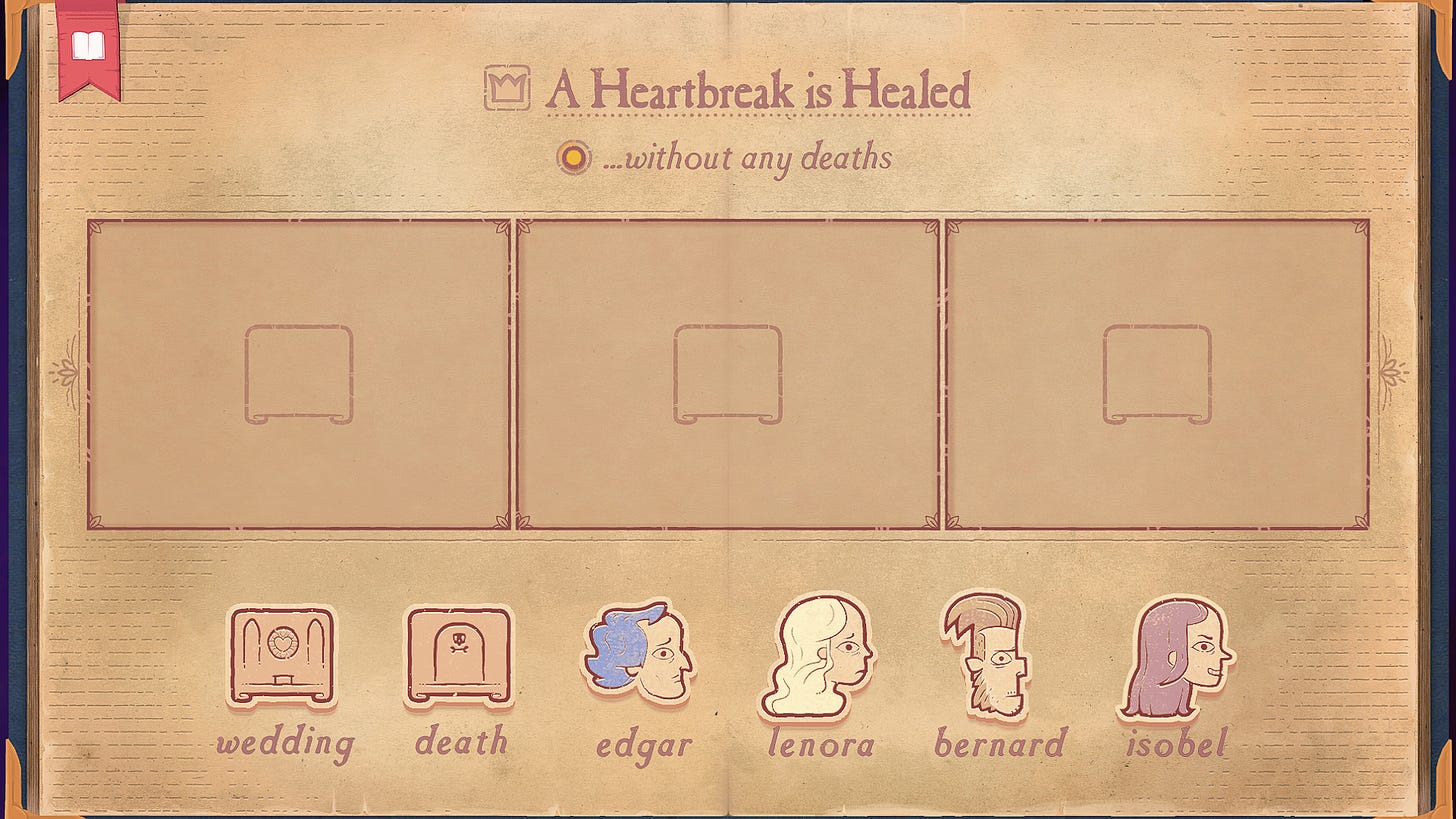

If you find yourself getting tripped up by the concept of narrative—the how of storytelling—the recent game Storyteller does a good job of breaking it down in a way where you can easily see all of the respective components of a given narrative and how they translate into a particular kind of story, indicated in game by the title of each level. Each of the elements are distinct and legible: the characters, what they might be doing (marry or die), and the number of story beats that go into making a complete, if simple, tale. And because this is presented as a comic strip, the player can use their existing knowledge of narrative structures and how to read them to superimpose that on what they need to do in game.

Play and Interplay

“Articulation” is just a fancy word for “joint,” and this is important, because gameplay articulations, much like shoulders and elbows, also make use of a fixed range of motion: a range, because you can place wedding in any or even all three of the frames, but also fixed, because you can only place wedding in one or all three of the frames. Articulations indicate both possibilities for play but limits as well. And so, in this establishment phase, you need to think conscientiously about what the player can do as well as what they can’t.

The can category, in this instance, has two conceptual modes: directed and undirected. The title and subheading give the player two directed modes for how to approach the level: you’re given the “end,” and your task as a player is to determine what the beginning and middle out to be in order to reach that end. The undirected modes are a little trickier. On the one hand, you could try out any of various arrangements in hopes of completing non explicit Steam achievements. In that sense, play is still semi-directed. But you can also, of your own volition, try a number of arrangements to see what kind of story results from it. Nothing in the game will pat you on the head for doing so, however. You need to find some intrinsic motivation.

Limitations, on the other hand, are often explicit but not telegraphed. The player tries to do something, and it just doesn’t work. That’s how you learn what you can’t do. From a design perspective, though, you have to determine how many characters you can include in a single panel, in this case two, and what types of relationships are acceptable. Storyteller doesn’t loudly trumpet this fact, but it is not heteronormative in its romantic assumptions. You can complete the level by having Edgar marry Bernard in panel 1, have Edgar reject Lenora in panel 2, and have Lenore marry Isobel in panel 3. Having men only form relationships with women would be a limitation the designer would have to impose, with obvious bigoted consequences.

System of Systems

Storyteller is, in so many ways, a game about reading and interpretation. Much like games such as Disco Elysium and Citizen Sleeper, it foregrounds its systems and how they interact. This primarily takes the form of a series of puzzles, with the individual “pieces” clearly delineated, but it draws upon certain assumptions about narrative structure the game anticipates its player possessing. If you’ve never seen or read a comic, for instance, what you see on the screen might look very strange.

So, it might be helpful to think of articulation as operating on three overlapping levels:

Between object and some framing device, like a piece of gear and an item slot

Between objects, when combined, for instance, in a crafting interface

Between game elements and player, as noted above

In Storyteller, the first level of articulation can be seen in the way scenes are placed within the framing element of the individual panels. On the other hand, characters cannot be placed into frames, unless a scene has been placed first. This is because the characters’ primary articulation is between objects, between character and scene. Additionally, fully composed scenes, with background and character elements, articulate with one another to form the transition between individual story beats.

Before we bring things to a close, the last thing we want to leave you with is to be careful that your assumptions about the player and your anticipation for how they will use what you provide doesn’t bleed over into presumption. It’s one thing to, for instance, develop a catalog of in game items that cater to or maybe even predetermine certain character builds. Cutting off certain avenues of gameplay probably won’t have dire consequences. However, if a game like Storyteller were built with certain heteronormative attitudes in mind—in the year 2023—you might risk alienating players you otherwise bear no ill will toward.

Don’t be that guy.

Next Time…

Barring another last minute change of heart, in next month’s post, we’ll consider the ways games complicate their established parameters in order to create engaging gameplay and elicit a broad spectrum of emotions. We’ll discuss the concept of ludonarrative irony in greater detail and use it as a framework for understanding and creating complex plotlines and encounters.

In the meanwhile, you can listen to Lauryn and Nicholas hash things out on the Furidashi Podcast, and, if you’re a theory nerd like we are, sign up for the Patreon, where we really get into the weeds. No pressure, though, no matter what you choose to do, we’re glad you’re here and hope you stick around.

Until next time!