Level Design and Narrative Mapping: Establish - Complicate - Resolve

An introduction to the relationship between story beats and level design

Because, as players, we experience time in linear fashion, you could say all story plots in video games are, in a sense, linear.

Even 3D environments are often explicitly designed with a linear structure in mind. The level starts you off on one side of a box, and you’re trying to get to the other side. Your path through that box might be circuitous, or it might be direct, but it is, in the end, a line. And so, in the most basic sense, your progression through that box is linear.

Level as Story/line

Lately, I’ve been working on a digital version of the tabletop game I designed late last year. UrbanPlan has been on hold, due to unforeseen issues, so instead I made a game called Snow based on using card draw mechanics as a means of telling a procedurally generated story through the accumulation of narrative snippets. Since it looks better for my portfolio to also have at least a prototype of a video game to show people, I decided to try and adapt Snow into a game for PC.

While working on Snow, I started putting together some mockups for level designs, and it occurred to me this would be an excellent occasion to discuss the relationship between the structure of story beats in a game’s narrative and the structure of a given level.

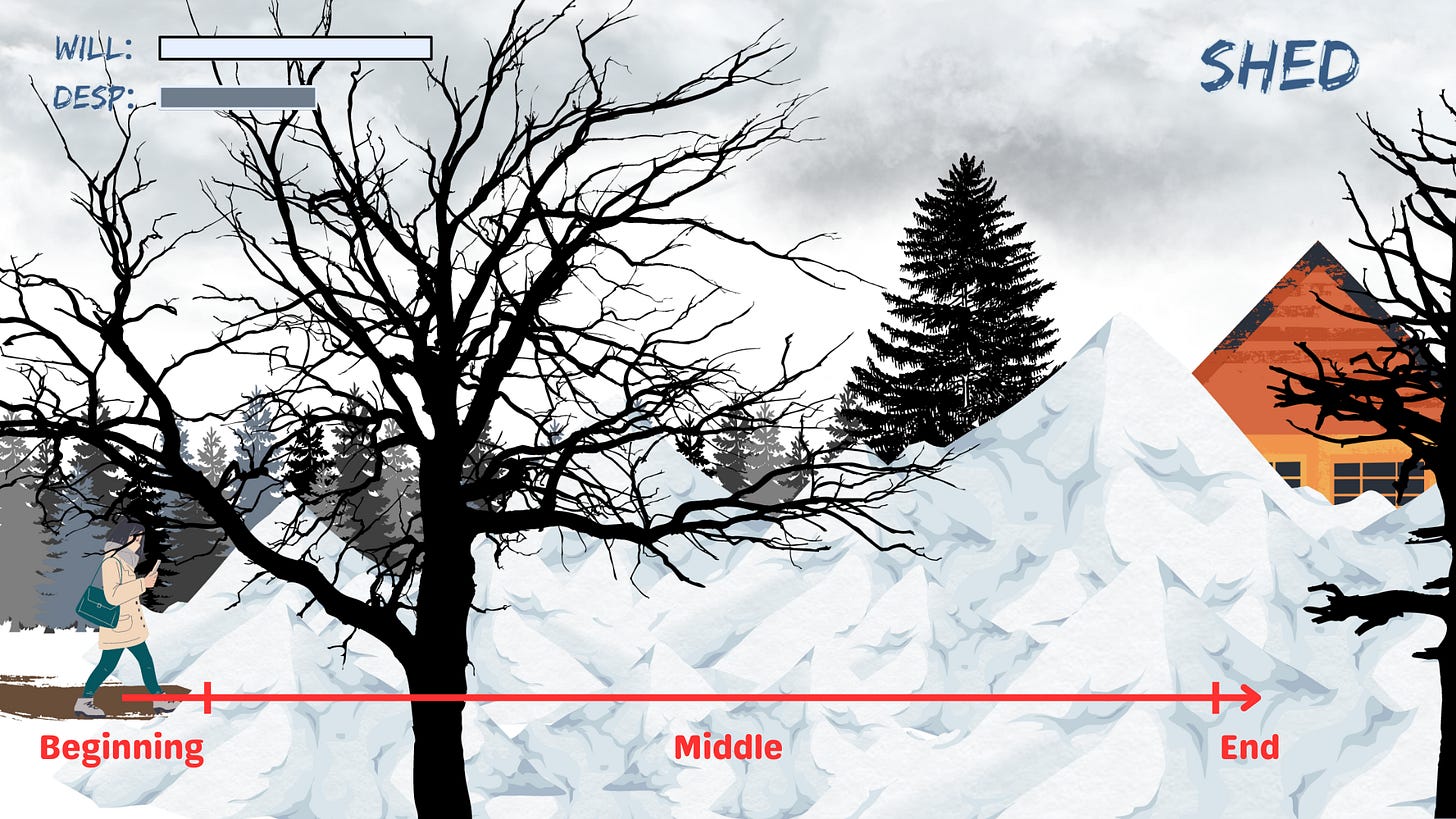

I’ll explain the two resource bars in a post further down the line, but for the time being, I want to focus on our avatar, “Lauryn,” and the snow drifts they’ll have to remove in the middle of the screen, before moving on to their objective, the shed on the far right. The trail Lauryn uncovers as they clear snow away and move to the right serves as an incidental progress bar the player can follow as they play. The game mechanics that pertain to this screen are relatively simple: you move in proximity of a snow drift and dig to clear it away. To be able to move to the shed, you have to remove all the drifts.

However, there’s another way to think about progression in this level, one that accounts for the level as a part of a larger narrative system and therefore integrates storytelling beats within it.

For the most part, plots have a beginning, a middle, and an end. Since we have a linear progression from left to right, this means we can map that simple linear plot structure onto our movement through the level. Likewise, the beginning can map onto what we initially encounter, our avatar Lauryn; the vast middle onto the majority of how we will be spending our time here, removing drifts; and the end onto the objective, the shed.

But a plot isn’t just an ordered list of events, and gameplay isn’t just a repetitive series of actions. A plot is also made up of the relationship between events, like if events are related in or out of chronological order, and how together they contribute to an overall sense of what the narrative is trying to achieve. It means something very different if a character gives up at the beginning of a story than if they give up at the very end, even if the action or plot point is identical in each instance.

Level as Narrative Motivation

With this focus on meaning and purpose, let’s think of our beginning, middle, and end in slightly different terms.

As Lauryn moves into the level from the left, that action establishes their place within it. As they move into the drifts and clear them, that represents an impediment or obstacle to their easy progress toward the shed. Reaching the shed resolves the tension created by that impediment by creating circumstances in which the clearing away is no longer necessary. It now has a purpose: the shed is no longer simply where forward progress happens to end, it is now what the player wants. We want to know what’s inside. Thus, the removal of the drifts become not simply a laundry list of tasks to perform but also a frustration of that desire to know. The harder they are to get through, the greater the tension, because you want to make it through to the other side.

This function can be seen just as commonly in 3D, open world games as the 2D sidescroller I’m currently working on. In Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild, you occasionally come within proximity to the various shrines you collect as you move through the world. You spy it in the distance, and that establishes your initial relationship to the shrine as well as the desire to seek it out. However, the contours of the world in between where you are and where you want to be complicate your progress toward the shrine and frustrate any desire to add its fast travel waypoint to your map. Reaching the shrine resolves that frustration, and you can now go back to dealing with the divine beasts.

I hope this example makes clear that the landscape of an open world is not just a container in which gameplay happens. The environment is motivated, by which I mean it scaffolds the very structure of desire and release that gameplay enacts. Recognizing this fact can then help us see how narrative can also be structured to scaffold gameplay or, perhaps, complicate it in a different way.

Establish

The initial moment within a level should, ideally, establish two things: 1) what the level is at that moment, as well as 2) who you or your avatar are within it.

A brief snippet of text can help reinforce where we are within the current level, within the story of the game, and even add a bit of characterization. I’m not saying what I have here is genius, but it does show how all these supposedly disparate aspects of a game feed into one another, creating a kind of superstructure that each of the individual structures of level, story, and mechanics clearly reflect.

Complicate

Our establish snippet says almost nothing about how we will progress toward our goal, even as it sets out what that objective is. The complicate phase, then is meant to enact that how, hopefully in a more interesting manner than moving quickly from left to right.

Another snippet of text, but this time it serves to explain why you can’t just move directly to a resolution. And again it provides a bit of characterization, nothing mind blowing but more than what would be apparent from simply observing Lauryn as they dig their way through the snow drifts. Thus, the complications both reflect the actions the player takes within the vast middle but also, through the addition of storytelling beats, build upon it.

Resolve

A resolution may seem straightforward, but unless it comes at the very end of the game, it really needs to do two things: 1) resolve whatever tensions resulted from the preceding complications and 2) transition to whatever follows.

The objective within this level is the shed, but the shed itself introduces a new cycle in which we will have a renewed beginning, middle, and end, at least in microcosmic terms. Here too, in the layout of the level, we can see that progression meter in the form of the trail left behind by clearing the drifts. With this basic structure in middle, the story beats we insert can be as straightforward or twisty as we choose them to be.

Again, we can see this play out in even the most expensive games to produce. Think about any given room in a Halo level. Upon entering, you get either a brief cutscene or Cortana talking in your ear about the situation as it stands. She establishes the scene and directs you toward whatever complications stand in the way of your forward progress. Maybe a lift has been depowered, and you have to activate various switches to turn it back on. Along the way, you might have to dispatch various Covenant soldiers who stand in your way, further frustrating your forward progress. Once the lift is powered, all that tension gets resolved, for the time being, as you move onto the next area.

Next Time…

So far, this has just been an overview of how to approach mapping narrative onto level design. Next time, we’ll get a bit more into the weeds concerning how to deal with that vast middle, how to nest narrative structures within one another, and how, generally speaking, to visualize story beats in order to break up monotony and reinforce what you’re trying to achieve in other aspects of gameplay.

See you then!