The Problem of Immersion in Cyberpunk and Beyond

Cyberpunk 2077 is about more than just being a spikey haired cyber guy... with a cyber shield. In fact, it's probably about too many things.

[This is a companion piece to our most recent Furidashi episode, which isn’t necessary listening for understanding what follows but does go into more depth regarding things that are only touched upon here.]

Content warning: this post deals briefly with sexual assault

The funny thing about discussing the concept of immersion in a more analytical vein is that there are almost too many points of entry. Certainly that’s one of the hallmarks of the now largely deprecated genre of the immersive sim: you’re given something to traverse, be it a level or a plot, and the game provides you with multiple parallel but interconnected means of doing so. These many pathways correspond to the many identities you could potentially adopt for your avatar. A stealth focused build many be more your speed, and in choosing that, you adapt yourself to a particular way of understanding and moving through the gameworld. You see things very differently from someone who might prefer a bruising, tankier build, who has little cause to be examining every room for cover and shadows, when they can just barrel on through.

Similarly, when trying to conceive of this post, I kept getting caught up in a number of analytical pathways that correspond to many different interests I’ve had over the course of my life. From my days as an academic and scholar of poetry, I thought about Susan Stewart’s Poetry and the Fate of the Senses, and how immersion engages in a kind of ironic play upon how we perceive the world around us. From my time doing lighting and sound design as a teenager and young adult, I think about the more technical aspects of how you manipulate real time experiences to construct an alternate vision of the world. From working on my own games, I think quite a bit about how SF tropes can be used to interrogate who we are and what we become in a world that is, at times, deeply hostile to our existence. And from just being alive for forty-six years, I’m struck by how weirdly nostalgic so much SF is these days, in a genre that was always known for how it tried to look forward into the future’s abyss.

But, of course, because I’m me, I also spent far too much time thinking about an old Strong Bad email from when I was in college. It’s about video games, and while musing about what he might be like in a video game, Strong Bad conceives of a vector graphics game in which he’s a giant floating head and the player is some kind of cyber guy… with a cyber shield. He’s quick to point out that the player does not control him in the game—“because you can’t control me!”—and there is this humorous tension between imagining himself immersed in and the central concern of a video game while also insisting that it never determines who he is.

So, you can see there are too many points of entry. Maybe we should just start with nostalgia. It’s as good a place as any.

Reactionary Futurism

Fascists love tradition, but because fascism itself is a post facto reaction to the many dysfunctions of liberalism and because in the first half of the 20th century it was a very new ideology, it has to invent the very traditions it proposes a return to. As Umberto Eco noted, fascism is mercurial, it’s steeped in ironies, but the contradictions never quite synthesize. It longs for a return to some glorious past, but it can only get there by radically transforming society into a kind of farcical mimicry of historical social relations that doesn’t really value the kinds of things people actually did in the past. It’s why you get these perverse movements like anti-vaxxers or raw milk weirdos, who more closely resemble homeopathic hippies from the 1960s than the “pioneer” ancestors they claim to be looking back to. It never occurs to them that their ancestors had to live with the realities of childhood mortality and foodborne illness and were more than happy to adopt the technological advancements that largely eradicated them.

Okay, but what does that have to do with Cyberpunk 2077 or immersion? For better or worse, Cyberpunk’s worldbuilding is a creature of 1980s and ‘90s geopolitics, because that’s where the origins of the pen and paper game lie. It seems sort of silly, given Japan’s trajectory since the ‘90s, to imagine all powerful Japanese corporations dominating the American landscape, but there was this very real yet wholly imagined fear that American capitalism had grown stagnant and was going to be overwhelmed by the “superior” corporate culture of the Asian behemoth. Of course, as we now know, the Japanese economy was, in a sense, a paper tiger, sitting atop a real estate asset bubble that, when it popped, took a decade and half to fully recover.

Cyberpunk’s Arasaka is a strange continuation of a geopolitical anxiety that even in its historical moment was a fiction. You could argue that the instability of the Japanese economy was not widely recognized at the time, but you could argue the projected domination by an “invading” or “foreign” element didn’t even make sense on its face. Did Japan have a globe spanning military to contain the “threat” of communism? No. Was oil suddenly going to be traded in yen instead of dollars, when Japan produces no fossil fuels besides coal? No. Was Japan suddenly going to come to dominate a global banking system with its tangled web of tax havens and forex markets? Of course not. The BRICS coalition has tried for some time now to dispute dollar hegemony and has met with very limited success. Japan was never going to be able to achieve what (mostly white) Americans feared would be the future.

But what was once a reflection of certain contemporary anxieties in SF—Marge Piercy’s He, She, and It is another notable example—nowadays is a peculiar relic that unnervingly conjures the specter of the very fascist tendencies that lurk with the Western “fandom” of Japanese cultural products. Arasaka is more feudal clan than modern corporation, curiously oblivious to how Japanese companies are actually structured, both then and now. It fails to recognize how Japanese corporatism since the 19th century is an explicit rejection of the feudal social order, as can be seen most clearly in the writings of Fukuzawa Yukichi, whom most people probably know from his picture on the 10,000 yen banknote.

What Arasaka imagines for the player is a kind of reactionary futurism grounded in half-baked ideas about Japan filtered through media imports and homegrown speculative stories about the mysterious “East.” This is because Cyberpunk’s projection into the future is grounded in a profoundly nostalgic worldview. It takes for granted the ‘80s obsession with rampant crime and urban decay in a contemporary moment where, in the US, violent crime has been on a steady decline for decades. Even as it updates the gameworld’s tech to more accurately reflect what we deal with now—ubiquitous smartphones, for instance—it never manages to slip free of an ideology that sees this incredibly violent, sexist futurepast of anomie as fertile ground for what we, as atomized individual human beings, might become.

Perhaps it’s time to take a step back and name one of the fundamental contradictions we’re grappling with:

Denial and Realization

Reactionary ideologies function only so long as they can persist in a potentially unconscious denial of a legible, documented past in order to fashion or realize a purely imagined one. This imaginary history and its attendant tradition, then, are projected forward into a longed for future where the real political binds of the current moment can simply be overlooked in favor of a “new” that the powers that be can keep under their control. Reactionaries like to fashion themselves as the protagonists of reality, and I think it’s no coincidence that NPC has entered the hard right political lexicon to describe the vast, unwashed masses of people that the fascist seeks to segregate himself from.

Much like the immersive sim, reactionary ideologies are a kind of escapism. And I think it’s no coincidence that games like Deus Ex are awash in the kind of conspiratorial thinking that the politics of reaction tend to breed. It’s the same kind of thinking that obsesses over an all-powerful though somehow simultaneously feeble other that controls the inner workings of society and must be rooted out. For the Nazis, it was the Jews and communists. For more recent rightwing movements, it’s the “cultural Marxists” who control the vast shadow bureaucracy dubbed the “deep state.” For JC Denton, it’s a confused panoply of aliens, revolutionary gangs, a rogue AI, and the Illuminati. For V, it’s a secretive corporation whose murdered former leader was trying to develop a technology that would make him functionally immortal.

Arasaka Saburo’s experiment is the catalyzing event that kicks off V’s psychic conflict and cooperation with the engram of Johnny Silverhand slowly taking over his/her body. Shadowy conspiracy and the reactionary politics that so often gravitate toward it are at the heart of the identity crisis V and by extension the player must face throughout the game. Cyberpunk’s many paths of player progression and narrative are rooted both in an ideology of individual exceptionalism (“becoming a legend”) and in the way that individual defines themself within the context of and largely in opposition to a “more real” reality that lies below the surface of ordinary relations.

The Futility of Good Violence

It’s worth noting that Cyberpunk 2077 the game, not the cultural phenomenon, starts the player off in a world very different from Denton’s. As part of a UN police force, JC is already embroiled in his world’s larger machinations, even if he doesn’t yet understand to what extent, but prior to taking up with Jackie, V is already down and out. As a streetkid, she—I played as female V, so I’ll be sticking to that from now on—gets screwed over by a job gone bad. As a corpo, she ends up on the losing end of an internecine fight within Arasaka’s security service. And as a nomad, she starts off on the very fringes of society. In each case, the driving motivation of her origins is to lift herself from her menial circumstances with the expectation that she could be fucked over at any moment.

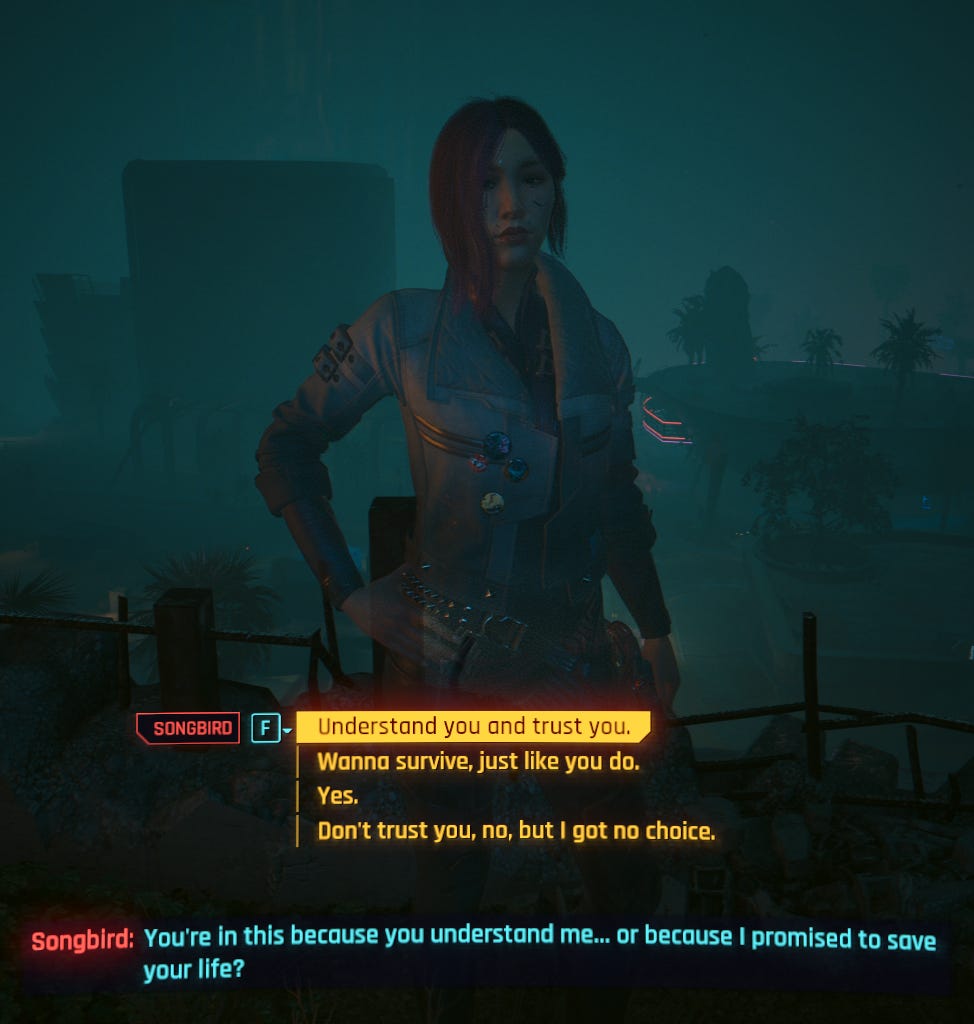

Yet, at the same time, there are numerous opportunities provided to V to try and find a genuinely human connection to other people: as partners in crime, to be sure, but also as a way out of the bind of simply being a mercenary for hire. It’s even possible, though Johnny never really stops being an asshole about it, to get him to come around to caring about you and what will happen when he’s no longer in your head. Or not. It depends on what you choose to do.

I mention the way the game treats these origins to highlight how, unlike many cyberpunk protagonists, V finds herself embroiled in the larger forces of the universe purely by accident and spends most of the game trying to extricate herself from it. She doesn’t want to be part of the bigger picture—in most narrative paths, at least—she wants to be herself again.

Now, you could make the argument that this is just Johnny Mnemonic with Keanu Reaves in a different role. A job goes very wrong, and our hero winds up with something in their head that they are desperate to get out. Cue the industrial music and weirdly tight plastic clothing. But where Cyberpunk 2077 differs from the media it looks back upon lies in how it actually dramatizes the dialectic of denial and realization. Actual, other-murdering Fascism cannot engage meaningfully with nuance or complication. It can’t ever admit that its fictive realism may not accurately describe the world around us, because that might put a halt on the radical, violent transformation of civil society it seeks to enact. If that train starts to slow down even a little bit, the paranoid foot soldiers of the hard right will turn on each other in an effort to prove they are the truest believers.

So, while I framed this discussion of cyberpunk in terms of its reactionary tendencies, lest we ever forget them, the game Cyberpunk 2077 has mixed feelings about aestheticized violence and about its power to enact an individual’s will upon the world. Judy’s questline, for instance, is replete with violent overthrows that, in time, fester and fall apart. You meet Judy through Evelyn, a femme fatale type who works with you to pull off a heist in Arasaka Yorinobu’s penthouse. That heist goes awry, of course, and the fallout finds Evelyn ping-ponging from one abusive situation to another. Judy’s whole questline is kicked off by V’s helping her to try and save Evelyn.

And you do save her eventually. But the violence perpetrated against Evelyn leaves its mark, and she chooses to end her suffering by ending her own life, leaving you and Judy to pick up the pieces. Initially, this takes the form of revenge on the man at the Clouds club who repeatedly assaulted Evelyn, but even in success, Judy feels hollow. Then, she tries to organize a takeover of Clouds by the “dolls” who work there, and though you initially succeed, eventually the criminal gang who controlled it before reassert themselves, killing several of the dolls who rose up in the process. Through Judy we see a cycle of presumably virtuous or at least justified violence—killing Evelyn’s captors, killing her abuser in revenge, rising up against the Tiger Claws—repeatedly engender the downfall of the radically new conditions it sought to bring about.

If that’s where things ended, though, with everything turning to shit, Cyberpunk 2077 would be fully in line with the kind of nihilism that pervades cyberpunk media. Instead, the questline culminates in a date with Judy, where the two of you dive down to where she grew up, a place now submerged by a massive polluted reservoir. You experience her memories through a special synced braindance recording and through this dual reminiscence gain a modicum of what motivates Judy and in some cases hold her back.

You could read Judy’s repetitions of revolutionary violence as a form of denialism and the return to a hopeful, if deluded, projection of a better future, the kind of realization I first identified with a fascist worldview. But where we end up with her is not yet another irrational movement forward but a return to a point of origin to derive a deeper (get it?), truer meaning that engages with the reality, not a fictive projection, of the past. So, when V experiences one of her many seizures underwater, and Judy has to haul her out in order to save her, we don’t get a repeat of what happened with Evelyn, in part, because no violence was involved. And, if you so choose and happen to be playing a female V, this questline can culminate in a sexual encounter with Judy and the beginnings of a romantic relationship with her.

This is a notably peculiar narrative path in a game that is so riddled with visceral, aestheticized violence, a game whose very “coolness” depends on how wicked sick it is to use a sniper rifle to make someone’s head explode or literally dismember gang member. You can actually spec into dismemberment. In that context, what could this simple moment of human connection mean? Well, first of all, maybe there is no simple answer. There is no Judy ending to the game in the way there’s a Panam one. And even if you end up in a relationship with our nomad queen and go storm Arasaka tower together, the only thing the game offers that relationship is escape, one in which V will shortly die from the many complications of having Johnny Silverhand in her head.

The game seems to say, “you can try and deny your part in the grand scheme of things, but reality will fight back. You can’t win.” If, in the end, you choose to keep your body, you wind up unnervingly like Evelyn. You tried to do something radical to change your circumstances, but your success means living only a brief while longer, maybe with your new girlfriend, and ultimately away from the only life you’ve known throughout the game. It’s bittersweet at best.

The Mechanics of Escape

We should probably take stock of where we are in this argument, since I can already see how long this is going to get.

The idea that violence can be used to bring about a radical social transformation, when operating from a fundamental denial of historical conditions, is pretty fashy.

Yet, because denial and realization remain in tension with one another, it’s always possible to go back and ground one’s future vision in something profoundly real.

On the one hand, Cyberpunk 2077 says again and again that this is just what cyberpunk media is like: it depicts a fallen society, so of course it’s going to be rife with violence, sexual coercion, addiction, and many other sources of misery. But it also says, “things don’t have to be this way.” The game’s focus on exodus and escapism as a way out of the many immiserating excesses of this world implies, to me at least, that there is an outside of cyberpunk’s overwhelming brutality. It might be Arizona or a found family or uploading your consciousness to the dark corners of the net, but there is a beyond that V can aspire to, even if it’s not the one she’d been seeking throughout the game.

It’s easy to see charges of “escapism” as a damning critique, but I want to bring in another perspective on escape, deeply rooted in SF traditions [sic], from noted anarchist and feminist author, Ursula Le Guin. In a blog post from 2011, she tackles the question of escapism in fantasy literature directly.

As for the charge of escapism, what does “escape” mean? Escape from real life, responsibility, order, duty, piety, is what the charge implies. But nobody, except the most criminally irresponsible or pitifully incompetent, escapes to jail. The direction of escape is toward freedom. So what is “escapism” an accusation of?

“Why are things as they are? Must they be as they are? What might they be like if they were otherwise?” To ask these questions is to admit the contingency of reality, or at least to allow that our perception of reality may be incomplete, our interpretation of it arbitrary or mistaken.

I know that to philosophers what I’m saying is childishly naive, but my mind cannot or will not follow philosophical argument, so I must remain naive. To an ordinary mind not trained in philosophy, the question—do things have to be the way they are/the way they are here and now/the way I’ve been told they are?—may be an important one. To open a door that has been kept closed is an important act.

Upholders and defenders of a status quo, political, social, economic, religious, or literary, may denigrate or diabolize or dismiss imaginative literature, because it is—more than any other kind of writing— subversive by nature. It has proved, over many centuries, a useful instrument of resistance to oppression.

“The direction of escape is toward freedom” is the kind of thing that seems obvious on its face, once you say it, but every day we say things to ourselves like “that’s just the way it is” or “some things you can’t change” in order to cope with difficulties we face in truly committing to an emancipatory ethos. What Le Guin implies here is that the first step in moving away from this fatalistic line of thinking lies in being able to imagine that it could be something else. Anarchists are sometimes fond of saying, “you have to kill the cop in your own head,” meaning, to be truly free, you must first dismiss that part of yourself that polices the limits of the possible, that tells you, “this is the way it has to be.”

The outside of brutality that I mentioned above is not merely a narrative endpoint in Cyberpunk 2077, it’s something built into the very mechanics of the game. You don’t have to kill everyone who stands in your way, you don’t have to spec into dismemberment, you can, if you choose, move through the game’s world in such a way as to deny, positively, its abject cruelty. You can sneak past the guards, steal the data, and get out. You can knock people out instead of killing them. You can talk your way out of a sticky situation. You can even find love.

At the same time, this isn’t a game like Undertale or Deltarune. You cannot be a pacifist in the absolute sense, because in order to progress in the main story, there are times when you’ll have to fight your way past someone. What’s more, there’s little in the way of ramifications for choosing to be a goody two shoes. Sure, if you start blasting people in what was supposed to be a stealth mission, you might get some mild chiding from an NPC, but that’s about it. Doing the mission as intended might get you some bonus pay from the fixer who hired you, but you’re never going to get the moral implications of acting non-violently like in a Toby Fox game. Your only lasting reward is the knowledge you were less of a piece of shit than the game allowed you to be.

Sometimes, the lack of ramifications border on the farcical. If you botch the infiltration of Hansen’s tower and end up having to kill a bunch of guards, the game tries to gesture toward fallout without ever making it fully stick, because that would ruin the narrative arc of the DLC. Hansen threatens you at the craps table, but after roughing Reed up a bit, the two of you are just let go. I suppose the walk to the exit on the ground floor is meant to feel ominous and intimidating, but because my build was arguably a bit overpowered, I just didn’t feel it. To check my suspicion, I loaded a save and managed to kill all of them without much difficulty, so Hansen’s threats felt hollow, because I knew on a mechanical level that he was no real threat to me.

The only time I ever felt truly threatened in the game was by the relic and, to an extent, by Johnny’s engram. Not only is it made clear early on that he can just take over your body, later, when he’s more “on your side,” he can still do things that unsettle V’s and my, the player’s, sense of self. In one mission, you give Johnny control of V’s body, so that he can get to Rogue and convince her to help. But when he does far more than he said he would, V can be—and I was—very pissed. And it wasn’t just about the pre-scripted dialogue options. Later, when my smart weapons didn’t seem to be working right, where my build relies on them, I realized it was because the tattoo that Johnny got while in control of V’s body had replaced the smart link cyberware that was a necessity for what I was trying to do with my character.

Despite my and V’s frustrations with him, I still couldn’t help but feel sorry for Johnny. He’s trying to escape you just as much as you’re trying to escape him. His escapades, despite being sometimes predicated on a lie, do achieve what both of you want… most of the time. And when you learn what happened to his body after the assault on Arasaka in 2023, it’s hard not to sympathize. Like Night City itself, Johnny’s influence is neither inherently good nor inherently bad, and the immersive sim-like qualities of the game make it so that you can choose to let that influence be a positive thing in the long run. Or not.

Sympathy for the Avatar

Most games, out of convenience or perhaps never giving it much thought, do little to tug on the invisible tether between the player and who or what represents them in the game. Your avatar becomes a kind of mask or persona—the Etruscan root of the Latin persona being the literal mask someone would wear in performance. This masking creates a kind doubled invisibility. You, a human being, as you are in the world, are invisible to those in the game you interact with, but the avatar herself is somewhat invisible to you as well. Through this invisibility, you can persist in the delusion that what happens in Night City is happening to you, not just to V. You can believe for a moment that it’s really you talking, because you’re the one making choices in the dialogue tree.

While I call this a delusion, I mean that about as neutrally as one can, given the word’s connotations. Because delusion here is much like Le Guin’s escapism, where the reality of how most people use the term belies something else that sits just below the surface. Le Guin reminds us that escape is always toward freedom, and I want to emphasize how delusion, losing yourself in the persona’s mask, gives you the freedom to do things in game that you are not otherwise capable of in your daily life. Many trans individuals have said that dressing up in gender non-conforming clothes helps them see something about themselves that was hard to identify in the context of a social milieu that denigrates their very existence and perpetrates immense harm upon them. Roleplay creates a space where, if only for a time, you can escape the dictates of the cop that society has stationed in your head.

But once again, Cyberpunk 2077 says a little more than just “isn’t it great to be someone else!” There are subtle indications that you as the player stand in a similar relation to your avatar, V, as Johnny does to her. And when Johnny takes over, we see, as from a remove, what the implications of that relationship are. As noted earlier, his ends may be the same, but his means have the potential to upset V and the player as well. He acts both in the collective interest as well as his own. If he does something in V’s body that she feels is a violation, what does it mean that we might potentially do something similar? All of this lies at the level of implication, though, as V never addresses the player directly to voice her dissatisfaction with choices we make on her behalf.

It’s hard to say whether the game could come right out and say it without ruining all those qualities that make it like an immersive sim. Immersion of this kind depends upon the actions of the player being synonymous with the actions of the avatar and their behavior a simple expression of our input. Perhaps, then, we should recognize how, unlike a classic immersive sim, there isn’t always a perfect correspondence to ourselves and V. Sometimes, her body glitches out, she has an attack from the damage the relic is wreaking upon her, or we find ourselves in another body entirely, as when we play through Johnny’s memories. We are mostly with/as V in the game but not entirely. There is just enough of an indication that something else might be going on.

It might be more appropriate to think of this avatar/player relationships, as well as the one with Johnny, as a kind of doubling, rather than a displacement. We are V and ourselves, so when the game does things to break the classic sense of immersion, it also highlights a more complex, nuanced idea of what immersion might mean. As someone who occasionally suffers from spasms and the rare seizure, I can say with authority that you get a very different sense of yourself when your nerves seem to be doing whatever the hell they feel like. You slip out of the illusion of a whole self identical to your conscious awareness and, in so doing, become more aware of subtle changes in your body that under ordinary circumstances you would just ignore.

Thus the doubling of Johnny and V allows us to see outside the avatar/player relationship we might take for granted and notice the subtleties of how we act with the avatar, not merely as them, even while that as-ness never completely goes away. It’s both. It has to be both, or else the very foundations of the game’s interactivity would disappear. We extend into V, V extends into Johnny, and the web of inter-action that results is, at the mechanical level, the indication that connection, not individual exception, might be the way out we need, if not the escape we want. Similarly, V’s connection to her companions, sharing their lives and their hopes, not just working a job, might be her only means of coming to grips with what’s killing her.

Conclusion

It’s no coincidence, I think, that the one person who does the most to pursue his own literal immortality, Arasaka Saburo, ends up very early on getting murdered by his son in a fit of anger. Alt’s immortality on the net depends on her shedding most of what makes her human. And the immortality of fame seems fleeting. Johnny may have blown up Arasaka tower, but he’s mostly remembered as a terrorist, if at all. Simultaneously, V and other characters are constantly confronted with death and have to deal with the pain of loss. If the game has a moral lesson, it would seem to be “how do you deal with the realization that all things must pass from this world?”

There’s that word again, realization. For most of this essay, I’ve used it to mean “making something manifest, a reality.” But its ordinary English meaning simply implies understanding. Another doubling: “making something a reality” implies but is also at odds with “making something understood.” Using V to engage in the usual power fantasy that games offer is at once opposed to the reality that events in the game are largely beyond your control but also necessary to arrive at the point in the story where the realization, the manifesting and understanding, of that reality can occur.

So, ironically, the denial of that reality, the hope that you can save V in the way she wants, not only makes it so that the game can play out, it also, through time and experience, helps us to mature to the point where we see more than what we presume to be the case. In a game where most of the time we’re expected to behave like a brutal, violent killer, one of the most important lessons we can learn from it is empathy. And the way we avoid the fascist trap of nihilism is by, like Judy, going back to the point of origin and grounding our denial, our escape, our movement toward freedom, in the truth of who we are, not a fiction with which to dominate the world around us.