The Gameplay Loop, But Different

Once again thinking about gameplay not as a movement toward some reward but a place to linger for its own sake

Longtime readers and listeners to the pod are probably aware that I have some quibbles with the concept of gameplay loops, in particular, the so-called core gameplay loop. Which isn’t to say it makes no sense or should be discarded but that it implies and in some cases reinforces a rather narrow conception of gameplay. But this is not meant to be yet another critique.

Without throwing away the loop as a productive concept, I want to bring to light some of the unexamined assumptions that underly it and, perhaps, think of another way to look at it that doesn’t see challenge and impediment as roadblocks to what players truly desire in a game, but rather as ends in themselves. I’ve written previously about how we might think of gameplay not as a means but as a site of the true pleasure in playing a game. People can get a little queasy when it comes to discussing pleasurable activities—due in no small part to an implied but rarely noted insinuation of sexual pleasure—but pleasure seeking activities are broad and, frankly, more than relevant to what we want when we seek to play a game.

The Loop and Its Effects

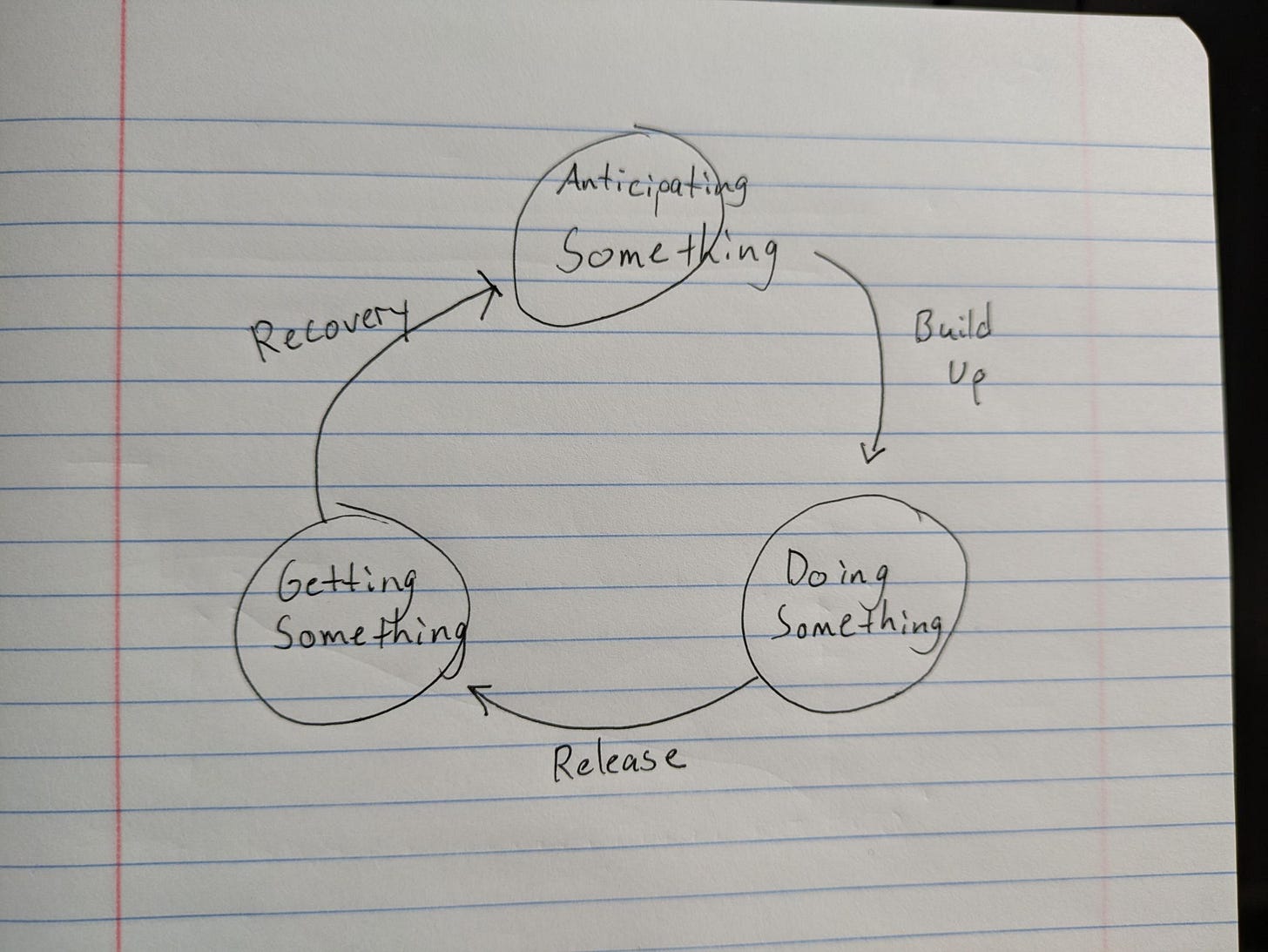

The loop and its attendant discourse gives us a way to talk about all this in a less sensual (boo!) and more technical way (yay?). Often, it simply reproduces the structure of what in psychology is known as a compulsion loop, which serves as the basis for describing the mechanics of behavioral phenomena like addiction or other self-destructive habits. It looks something like this:

I’ve tried to render this as something a bit more basic in order to show its broad applicability. Moreover, I’ve characterized the arrows between stages in order to show how this process does something to the player psychologically as well as physically. Same thing, really. We don’t go in for mind-body dualism here at Furidashi…

To explain this cycle, let’s use Hearthstone as an example. Let’s say your opponent goes first, and they play a couple cards, one of which puts a minion on the board and the other puts a secret in play. Unlike other card games, such as Magic: The Gathering, on your opponent’s turn, you just have to sit there while they play things out. While you wait, you anticipate what they will do as well as how you will respond when your turn rolls around. That’s step one in our little graph.

Then, you get to do something. That’s step two. You have the perfect response. You cast a spell to remove that minion your opponent played and proceed to play your own minion on the board. So, what you “get” out of this interaction (step three) is a superior board position to your opponent as well as the modest thrill of having pulled one over on them.

That thrill means that, in addition to the steps, there’s something else going on, indicated here by those three arrows. In the first transition, from anticipation to doing, there is a build up of stress and tension. This stress isn’t inherently a bad thing, as knowing that you have the perfect response to what your opponent is doing can actually be quite exhilarating. From doing to getting, we get a kind of release. The built up stress breaks in tension, and a number of psychological responses can result.

Typically, we experience a kind of elation, but the release can just as easily result in a kind of uneasiness or dissatisfaction. When you try something, and it doesn’t have the intended result, you might feel frustration or anger. Note how in the example above your opponent also played a secret. In your rush to remove the minion they played, you might have overlooked the possibility of a counterspell, negating the removal you intended to play, disrupting your efforts, and leaving you in a far less advantageous position than you otherwise were expecting.

Which isn’t the end of the world, of course, because you can recover, as you move from whatever you got to anticipating what the next moves will be. This period of recovery is necessary, because, as many loops pass, you might end up suffering from a kind of sensory overload. Your body can’t keep pumping you full of consciousness altering hormones, or else serious damage would result. That’s just basic homeostasis. Your body generally wants to return to a base state after stimulation.

Persistent Effects of Momentary Actions

According to the theory, a repetition of these loops goes on and on until some end state has been reached. This means alongside the loop mechanism there is a parallel mechanism of persistent effects that accumulate until they meet some arbitrary standard determined by the game. In Hearthstone, each player has a certain amount of health, and if that number goes to zero or less, the game is over. These persistent values are affected by what happens within the loop (i.e. doing something) but they are not subject to that gameplay homeostasis we identified above.

As an effect of this accumulation, consider how people get tilted. A series of setbacks in the release movement from doing to getting can build up over time and start to affect players’ judgment. Your opponent keeps countering your plays or sets up a board state for which you don’t have an obvious or even a good response. The psychological effect of this build up is so strong that not only can it persist outside the loop of one round of turns but even between games. You could address this problem directly by maybe taking a moment away from the game, or you can push through it, hoping the cycle of setbacks will break, and some success will diminish the impact of getting tilted.

Maybe this is the UX designer in me talking, but we shouldn’t treat these momentary and persistent effects on the person of the player as merely incidental. I know I’ve talked a lot on the pod about player subjectivity, but the reason why is that sometimes I get the impression far more of a game designer’s time is spent focusing on what appears in the circles—anticipating, doing, and getting—and far less on the effects those aspects of design have.

If you’re curious, and have five bucks burning a hole in your pocket, I talk in a recent Patreon episode about how Jesse Schell, in The Art of Game Design, looks down on dynamic difficulty settings and says it somehow takes away from what should properly be the designer’s purview. As a counterpoint, I talk at length about how Hades’ “god mode” seems to directly refute Schell’s claim.

The way it functions, it slowly ramps up the benefit to the player (damage reduction) every time they fail to complete a run. Thus, the way god mode works implies a latent understanding of how those persistent effects on the player’s psychology (getting tilted) can negatively impact the smooth implementation of the gameplay loop, especially one that embraces difficulty rather than eschewing it. To use another example, in Dota 2, if you manage to kill an enemy player who’s racked up a kill streak, you get much more gold than you might otherwise, because the game is trying smooth the frustration that comes from possibly getting stomped and provide a potential comeback mechanic.

I use these examples to illustrate how games can and do directly intervene in those transitions between points in the loop as well as the impacts they have on the player’s overall mental state. A more holistic approach to conceptualizing gameplay, then, would involve, first, understanding the game as something that happens between player and software/hardware rather than just the latter. And second, it would mean treating psychological impacts in much the same way as you might treat any other variable, like health or mana or action points or whatever.

The Waiting Is the Point?

The last thing I want to say, then, is that, much like focusing on the pleasures of gameplay itself, we might look at the ordinary gameplay loop not as a movement towards culmination or climax but as an accumulation or modulation of effects. Instead of a series of dopamine hits, what would it look like if games were focused primarily on what the player feels as they play, in the moment, instead of where they end up? I don’t have a definitive answer, but I want to posit a few examples as a way toward thinking about what a grounding framework might look like.

I spend a lot of time thinking about games other people REALLY like, but I kind of don’t. I’ve talked about From Software games quite a bit in the past, so instead I’d like to think about the effect of anticipation in survival horror games as well as why so many people spent most of their time in Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom building things rather than progressing toward the game’s conclusion. In each case, the doing itself, the being in game as it plays out constitute the primary motivating force for the player and not some eventual reward.

I’m probably one of only a handful of people in the world who didn’t like TOTK. I really enjoyed Breath of the Wild, but I found its follow-up to be mostly made of distractions. It’s not that building things in game has no relationship to progression. Quite often building something is a requirement for solving the game’s many environmental puzzles. But the puzzles themselves also felt like a distraction. You don’t really have to do the temples, but doing enough of them will help with completing the objectives that make up the game’s main storyline.

I was curious, though, why so many people never bothered to complete the game, despite spending a hundred hours in it, or for whom completing the game was itself the distraction from what they found fun. The construction system in TOTK plays into something that has been a recurring motif in Nintendo’s design philosophy, namely that a game can function in large part like a toy. The joy of gameplay, its pleasure, lies in the construction and manipulation itself and in using the things a player makes as a creative expression of their imagination. “What happens” matters less than “what can I do” with the pieces the game gives.

Even the “what happens,” though, can be understood as something beyond mere links in a great chain of loopy being. In games like Silent Hill and Amnesia, anticipation itself, as you see something horrific play out in your immediate environs, can become an end of gameplay. A hack way of understanding horror is that the potential victims hiding in a closet, as the monster searches for them, is just a waiting game before a jump scare or the monster discovering them, resulting in a frantic chase. In games, hiding moments quite often never culminate in anything, and successful execution of gameplay mechanics means remaining quiet or in hiding. Which leaves us with a question, then: what was the point of that experience if the presumed culmination never comes?

As it turns out, the moment of waiting in fear and anticipation was the point. Games in general condition us to understand that results can only be gleaned from actively engaging with what happens. Jump the platforms. Run and gun. Find the treasure. Kill the boss. But what survival horror games often demand is to resist this impulse, to dwell in the feeling, complicated as it may be, so long as the overwhelming danger is present. From a certain perspective, this might seem to be the very opposite of gameplay—you’re not really doing anything!—but from another, it’s seeing gameplay in a more holistic sense. From this perspective, we might start to see why so-called walking simulators are far from the antithesis of ordinary gameplay. Rather, they reveal, by going so far in the direction of passive, sensory experience, something that has been there all along.