Games: The Subjectivity Engine

While it's common to think of games in terms of a singular player experience, what would it be like to make a game whose focus is tweeking and expanding upon the player's perspective?

In this week’s Furidashi episode, Lauryn and I spoke at length about first person perspective in games and how to split FP, in a sense, into two distinct, often contradictory voices. As a result, we spent quite a bit of time talking about second person narration (“you find yourself in a dark wood, with two diverging paths…”) and how it implies the first person perspective, but from a remove. So with first and second person “voices” in a game, you get an interestingly bifurcated look at the same series of events from both a subjective and objective perspective: you feel the moment in your own terms even as someone else describes it to you in theirs. This means, as you play, you can be both in the moment but also outside of it, allowing you to at once focus on the action and reflect upon what it means.

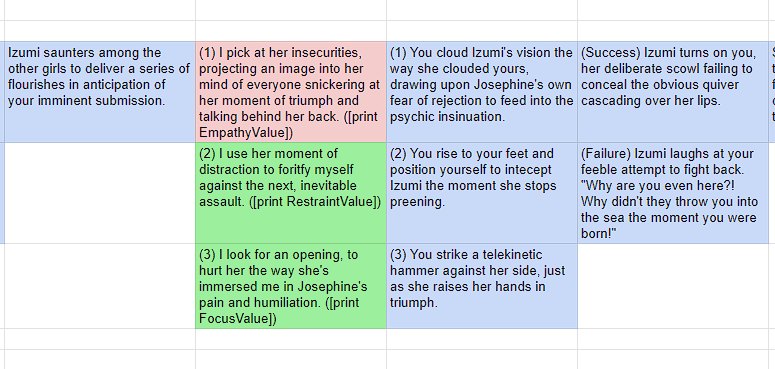

Maybe we should look at an example. Here’s the script for one decision point from an encounter in Act 1 of Le Concours des Filles (soon to be Sympathetic Memories):

This is the basic structure of each choice within the game’s encounters. On the left, Izumi preening among the other girls establishes the situation. The second column lays out your possible choices, the third tells you what happens as a result of that choice, and the fourth describes what succeeding or failing the skill check looks like. The choice itself is in first person and appears in game as a distinct overlay menu. The rest is in second person, although the very first cell here doesn’t indicate that clearly. In fact, if you look closely, you’ll see that what we have is, in fact, first, second, and third person narration all rolled into one. The purpose of this is not just to be confusing but to show a kind of singular condition between perspectives. We might treat them as distinct, but in reality they are just facets of the same whole.

Even though as you play, you’ll only get one particular throughline of the story, the matrix of how things are written here shows that there is a certain degree of replayability in how each hinge point in just this four part microcosm is key to how the narrative modulates from one moment to the next. And, unlike many other visual novels, there is no one correct or ideal path. All possibilities are true, just as we said in the podcast, all perspectives are true.

So, then, if the player experience is more than just a singular, subjective, “first person” condition, how else might we characterize this layering of narrative “modulations” in a game?

Intersubjectivity

Under normal circumstances, this is where I would wax philosophically, discussing the different ways intersubjectivity is defined in phenomenology and psychoanalysis, but it occurred to me this morning that there’s a much simpler way of describing it without having to get into the academic weeds.

Someone gets kicked in the crouch, and you immediately react. Your body closes and you feel something, even if it’s not precisely the pain of being hit in the junk. Why? This is not exactly a well-explained phenomenon, as neuroscience alone can’t quite cover everything that’s happening. Sure, the existence of motor neurons, neurons that respond to indirect, external stimuli, covers some of it, but intersubjective phenomena can be seen in a variety of cases where mere nerves are a paltry explanation.

You read a novel, and its tragic ending makes you weep. A friend describes an especially messy break up, and you feel intense concern for their well-being. You see images of children’s bodies lying limp after an air strike, and you feel a mix of rage and a sickness in the pit of your stomach. None of these things happened to you in the strictest sense, and yet you feel it, you experience it somehow, because subjectivity, the condition of the “I” or ego, isn’t nearly as discrete as some people would like it to be.

Though you could argue that games, with their emphasis on interactivity, are always making explicit use of this subjective slippage, some games, like The Last of Us Part 2, highlight an inherent intersubjectivity by forcing the player to experience the same moment from the perspective of two distinct and, in this case, conflicting characters.

The fight between Ellie and Abby functions as a kind of doubled climax. You fight it once with Ellie as the protagonist and then again much later with Abby as a kind of second protagonist. As a result, weirdly, the true protagonist almost becomes the encounter itself, a condition that exists between the two characters that requires both but cannot be sufficiently explained by the experiences of either. They are mirrors of one another, each seeking revenge for a death for which the other is at least partially responsible. At least in their eyes.

I don’t want to make too much of this, because, in my opinion, the execution doesn’t quite work, and the fight seems to echo an encounter in Part 1, which, if intended, I’m confused as to what the devs thought the player should make of it. Regardless, neither Ellie’s nor Abby’s perspective in the game can be entirely explained by what happens to them or how the player acts on their behalf.

In the vast preponderance of cases, games choose to simply sidestep whatever questions intersubjectivity might raise. NPCs only “exist” insofar as the player’s avatar interacts with them, and whatever incites about events may be available to the player by seeing things through their eyes remain either hidden or are deemed irrelevant. That is one means by which the game preserve’s the players sense of being the true hero of the story.

You Can[‘t] Tell Me What to Do

In the current game I’m working on, the second person narrative voice is pretty easy to understand, since it’s literally another character sharing the main character’s memories. In a game I made a little over a year ago, Snow, it’s a little more complicated, because the voice addressing the player is never revealed and could just as easily be interpreted as the avatar talking to themself.

I picked this card as an example, because it shows how second person address can have many valences. The narrative text, while feigning aloofness, has a tenor of self-justification and self-recrimination. It’s “stating facts” about your past, but in such a way that it’s trying a little too hard to be neutral. That neutrality is telling, because what’s being said demands far more than just a cold description, it demands empathy. And in its near refusal to empathize you get a pretty clear sense of the character’s headspace, how even as they dig up these memories, they sometimes refuse to accept the full weight of what they say.

That is then juxtaposed with the implicit “you” in the card text telling the player how this memory will affect gameplay going forward. Even though it lays out a pretty significant, lasting penalty, the tenor here is that of game rules or objectives: it’s about as truly neutral as it gets. Now, admittedly, there are some cards that step outside this neutrality, but it shows how the mode of address in second person narration can move the player through various subjective conditions.

In Snow, the memory cards are more like waypoints or objectives, something you’re working or moving toward, while the event cards give a brief telling of what happens from one day (i.e. round of play) to the next. Altogether, as you play, these vignettes make up the game’s story, in which the memory cards function as flashbacks. The tenor of this card is a little bit more difficult to identify, though, because, unlike the one above, its “neutral” tone isn’t really straining to resist in quite the same way. Moreover, when juxtaposed with the effect in bold text at the bottom—that is, no effect—there is more of a dark humor to the card as a whole where as the memory example is almost deadly serious.

So, already, we see three different modes of address in what is, ostensibly, the same voice. Just like with Ellie and Abby, the player’s subjective state is something that exists between various, seemingly contradictory moods and modes. And in this particular instance, it’s not just a mood I’ve constructed for the player, it’s a piece of me as well. Checking my blood pressure and navigating the benefits and drawbacks of various medications is something I have to do everyday. It’s not just a distant voice making a cheeky comment about normalcy, it’s me, the designer, the creator of this game, speaking directly to you, asking you to see what my life is like and perhaps empathize.

Conclusion

So, to wrap things up, what I hope I’ve shown is how the way games split what the player does into many subjective states isn’t a fragmentation or a shattering of the self into many disconnected bits, but a drawing in of many perspectives that are more or less complete in themselves. Many stories get drawn into a kind of constellation in such a way as to show how a singular, unified, and lonely ego is just a mirage. By constructing the “I” as a shadow of “you,” we are forced to confront how others see us, just as replaying the fight with Abby in the lead forces the player to confront the fact that she has been deeply hurt herself and that her actions are no less justified than Ellie’s.

This conception of intersubjectivity in gameplay, I hope, points the way toward other productive interactions in game design, like the need for careful, nuanced writing and talented voice actors to perform it. In Portal, not much is ever revealed about your avatar beyond little snippets here and there, and much of the onus lies on GLaDOS to define your place in this bizarre testing environment. This one VO performance alone, much the narrator in The Stanley Parable, elevates what could be taken as one long, cleverly constructed tutorial into an almost perverse meditation on the insignificance of any given individual, even as the game literally hands you the power to walk through walls.

That’s it for this installment, then. I guess we’ll back back next month to talk about historical and literary influences, if the pod sticks to plan. But since we often don’t, who knows what will be in store!

See you then!